Immobility captured on film

In his viva voce at the Academy of Fine Art just before the summer, Andreas Bunte presented his project Library for A-Scientific Film 2012–2015, which includes video art works that explore the aesthetics of old scientific research films.

Scientific film

After three years of work, Bunte was ready for his viva voce in the Academy’s auditorium, and to present his work Library for A-Scientific Film 2012–2015, which investigates the scientific films produced by the Institut für den Wissenschaftlichen Film (IWF), which was founded in former West Germany in 1956 and existed until 2010. The aim of the films made at this institute was to document every conceivable kind of motion in the most objective and

neutral manner possible, without music, voice-over, or personalised camera angles, in accordance with strict cinematic guidelines. No personal or emotional elements were allowed to sneak into these films. Andreas Bunte first saw the films as a school pupil, since they were frequently used as teaching material throughout Germany.

“There was always something I liked about these films. They do not attempt to overwhelm or entertain the spectator, the style of presentation is extremely dry and sober and that is why I became interested in them,” Bunte says.

Historically the production of scientific images built on the idea to document – through drawing or painting – the ideal example of a specimen. Such images were regarded as the truest possible representations of Nature, assuming that it was symmetrical, regular and rational.

“With the invention of the photographic camera, it suddenly became evident that nature did not conform to such ideals at all. The ‘mechanical objectivity’ of photography presented Nature as irregular, asymmetrical, chaotic. The first scientific photographs of drops falling onto a surface, for example, showed that the drops were not disintegrating symmetrically (as was the common belief), but that each drop showed a different asymmetrical disintegration pattern, and that none of them was identical.”

Avoiding parody and imitation

The Encyclopaedia Cinematographica, a special collection of films set up by the IWF, with the intention of providing an archive of scientific research films documenting every conceivable process on the planet: humans doing summersaults, birds flying, swarth forming during the machining of steel, or cultural customs in Papua New Guinea. In deciding to explore this genre, its concepts and aesthetics, Andreas Bunte had no intention of parodying or imitating it. The aim was to develop something new. The first two films he produced dealt with the physical phenomenon of pressure. They were a contribution to an exhibition on the theme of post-revolutionary states in society, that Bunte was invited to. Adopting a covert and indirect approach to the exhibition theme, Bunte filmed two former East Germany facilities, which recreated the high and low pressure that occur in nature, and the fates of which were strongly affected by the fall of the wall and the reunification of Germany. Künstliche Diamanten/Synthetic Diamonds and Unterdruck/Low Pressure (both from 2013) explored the production, respectively, of diamonds and athletes in the GDR.

High and low pressure

High Pressure is about the production of artificial diamonds using high pressure to transform one of the world’s softest materials, graphite, into its hardest, diamond.

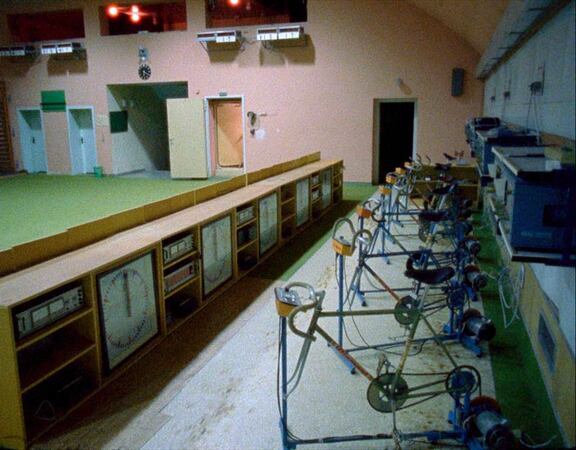

The research into the production of artificial diamonds was initially carried out at the East German Institute for Physics of the Earth. After the reunification the institute was discontinued and one of its researchers bought the machinery to established a private enterprise. Low Pressure shows a large low-pressure chamber where East German athletes trained for the Olympic Games and other elite sporting events. The chambers artificially recreate the conditions athletes would experience at high altitudes, conditions that didn’t occur naturally in the GDR. The film shows the now abandoned facility where athletes once sat bent over stationary cycling ergometers. The only sound one hears is the humming of the air-conditioning, and of electrical currents and transformers. A kind of Kubrick-like atmosphere hangs over the empty, monumental architecture in Bunte’s film.

“The IWF developed the concept of ‘Bewegungsdauerpräparat’, which considers film as a means to produce permanent preparations of motion. Low Pressure applies this concept to the subject matter of architecture, which, except for some flickering neon tubes, is devoid of any movement or change. Most scenes, at first sight, document a seeming ‘non-event’, the absence of movement, or change. What the film shows instead is the persistence of architecture – something that is normally hardly considered a process, because it does not involve perceivable durational change. Persistence is commonly only recognized as a time-based phenomenon through its opposite, the process of decay, the traces of which not only refer to the extremely slow process operating against architecture’s duration, but also dialectically emphasize architecture’s ‘still-there-ness’. However, the actual taking place of either architectural persistence or decay evades human perception as well as the gaze of a ‘scientific’ camera. Low Pressure nonetheless attempts to create a permanent preparation of motion of this process capturing significant sections of the duration of architecture and relating them to the time span of humans, to that of political systems, and implicitly to the time frame of geological formations, such as that of a 4,000 m high mountain that the building attempts to simulate.”

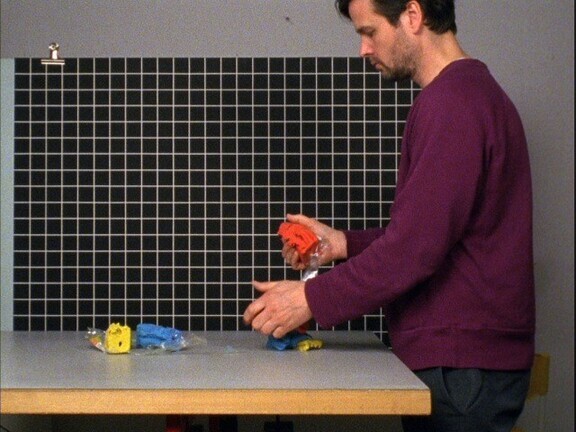

Bunte’s doctoral work also includes a film showing the disassembly of cluster bombs (Safe Disassembly, 2015) and a series of short clips documenting everyday activities such the unpacking of shopping bags, the disentangling of earphone cables or the swinging of a credit card, each task performed in front of a geometric grid of the kind used in the scientific motion studies. These films explore the field of tension between the generic and the specific through their particular form of presentation. The individual films were accessed through QR codes that had to be scanned with a smartphone or tablet. The codes were printed onto posters placed in particular locations in the urban environment, so that when standing e.g. beside a row of shopping trolleys one could scan a code and watch a film featuring the pushing together of such trolleys on one’s smartphone. This way, one reality was superimposed on the other, the generic met the particular.

Architecture in films

“Films about immobile objects, such as architecture, establish a different type of momentum than still images: There is always a potential that movement will occur, that something new will happen. One of the films that I produced as part of the fellowship focuses exactly on this momentum. It does not provide an account of visible change, but documents a process that is usually not considered an event: the persistence of architecture. As such the film plays with Scientific Research Film’s focus to document and make visible all kinds of movement. The persistence of architecture is simply too slow a process to translate in a filmic account of visible change.”

Bunte intends to continue his work on filming immobility, with the University of Vancouver as his next subject.

“My research into the films and concepts of the IWF singled out a number of access points for a critical re-thinking of fundamental aspects of filmmaking, and I would think that these can be developed further in future project. I have just finished shooting a film about the Simon Fraser University in Vancouver. The film with the working title Erosion will attempt to establish the architecture as geological formation, and explore how rain and fog interact with the concrete architecture of the SFU campus built by Arthur Erickson in the 1960s. This film will once more take a natural scientific topic as a starting point while following up on my interest in architecture in the widest sense.”

As a research fellow at KHiO, Bunte has spent three years working on the films, with funding from the Norwegian Artistic Research Programme. The Oslo National Academy of the Arts fellowship programme involves a three-year period of artistic study that is legally equivalent to higher-education research. In other words, the fellowship programme equates to research-based doctoral programmes in other academic fields. The unique feature of the programme is that it places practical artistic work at the centre of the fellow’s project.

Andreas Bunte’s viva voce took place on 10 May in the main auditorium at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts.

Assessment committee

Dr Renate Lorenz (chair), Berlin-based artist

Dr Thomas Elsaesser, professor of film and television studies at the University of Amsterdam

Florian Wüst, Berlin-based artist and curator

Supervisors

• Principal supervisor: Synne Bull

• Assistant supervisor: Gerhard Byrne

Short CV, Andreas Bunte

Lives and works in Berlin and Oslo

1991–1993 Fine Art, Gesamthochschule Kassel, Germany

1993–1998 Fine Art, Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, Germany

In recent years, Andreas Bunte has worked with experimental short films and film installation, often incorporating a range of other media, such as collages, architectural structures, sounds, texts, etc. At the heart of Bunte’s practice is an interest in the interaction between technology, architecture and the body, and how this interaction is reflected in our physical environment.